American researchers from Stanford University and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) of the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have combined gecko-inspired adhesives and a custom robotic gripper to create a device for grabbing space debris.

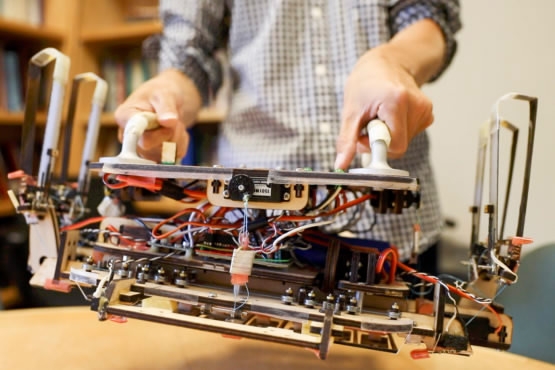

Close up of the robotic gripper made by the Cutkosky lab at Stanford University. The gripper is designed to grab objects in zero gravity using their gecko-inspired adhesive. /Stanford University Photo

For tidying up human-made debris in space, believed to consist of 500,000 pieces orbiting Earth at speeds of up to 28,160 kilometers per hour, suction cups don't work in a vacuum. Traditional sticky substances like tape are largely useless because the chemicals they rely on can't withstand the extreme temperature swings, and magnets only work on objects that are magnetic.

To tackle the mess, "what we've developed is a gripper that uses gecko-inspired adhesives," said Mark Cutkosky, professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford and author of a paper published in the June 27 issue of Science Robotics.

Research members test grabbing a heavy object in a simulated space environment. /Stanford University Photo

Geckos can climb walls because their feet have microscopic flaps that, when in full contact with a surface, create a Van der Waals force between the feet and the surface. These are weak intermolecular forces that result from subtle differences in the positions of electrons on the outsides of molecules.

The gecko-inspired adhesives developed by the Cutkosky lab have previously been used in climbing robots and a system that allowed humans to climb up certain surfaces.

The structure of a gecko’s foot, which contains thousands of microscope hairs. /VCG Photo

As the flaps of the adhesive are about 40 micrometers across while a gecko's are about 200 nanometers, the gripper is not as intricate as a gecko's foot but the adhesive works in much the same way.

Like a gecko's foot, it is only sticky if the flaps are pushed in a specific direction, but making it stick only requires a light push in the right direction. The pads unlock with the same gentle movement, creating very little force against the object.

Hao Jiang, graduate student in the Cutkosky lab and lead author of the paper, shows a basketball being gripped by the gecko-inspired adhesive. /Stanford University Photo

The gripper has a grid of adhesive squares on the front and arms with thin adhesive strips that can fold out and move toward the middle of the robot from either side, as though it's offering a hug. The grid can stick to flat objects, like a solar panel, and the arms can grab curved objects, like a rocket body.

Research members test gradbbing a heavy object in a simulated space environment. /Stanford University Photo

The group has tested their gripper, and smaller versions, in their lab and in multiple zero gravity experimental spaces, including the International Space Station (ISS).

Next steps for the gripper, now made of laser-cut plywood and rubber bands, which would become brittle in space, involve readying it for testing outside the space station, including creating a version made of longer lasting materials able to withstand high levels of radiation and extreme temperatures.

(Source: Xinhua)