2016年英国退欧公投表决以来,英国退欧反对派已经非常不满。3月23日至26日,距离英国预先安排的脱欧时间还有一年,英国基层民众纷纷上街游行抗议。

Opposition to Britain’s exit from the European Union has been vocal since the June 2016 referendum – over the next six months, moves to keep the UK from the exit door are set to intensify to a crescendo opponents hope will block Brexit.

From March 23 to 26, grassroots campaigners are hitting the streets of Britain to hold a series of rallies one year ahead of the country’s scheduled departure from the EU.

So what are their arguments, and what do the protesters hope to achieve?

Three arguments for a U-turn

Brexit supporters say that the people have spoken – the 52-48 vote in 2016 means Britain must leave the EU. Opponents contend that times change, people’s minds change, and Brexit is fundamentally bad for Britain.

The economic argument

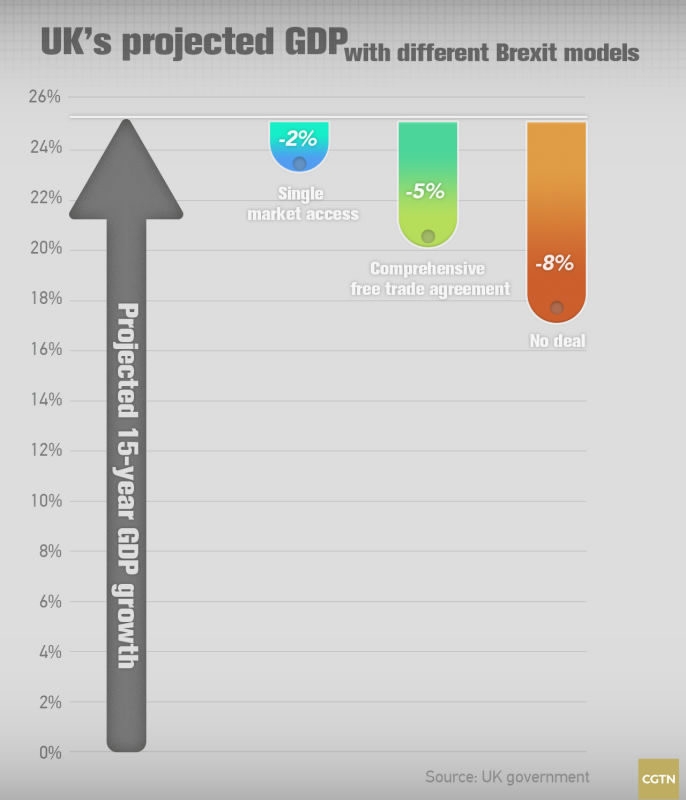

The central argument against Brexit is simple – Britain and the EU will be weakened economically by Britain’s exit. The UK government’s own economic risk assessments indicate that no matter what the manner of Brexit, Britain will be poorer as a result. many argue that misinformation from both sides of the debate in 2016 meant voters did not have an accurate picture of what Brexit meant when casting their ballots.

The security argument

Britain has been hit by several terror attacks since the beginning of 2017, plus the March 4 nerve agent attack which London believes Russia was responsible for. Security and intelligence cooperation between Britain and other EU members is a crucial part of the union. And even some who instinctively feel opposed to EU membership see a united Europe as a necessary bulwark, blunting rivalries within the bloc and standing up to large countries outside.

The generational argument

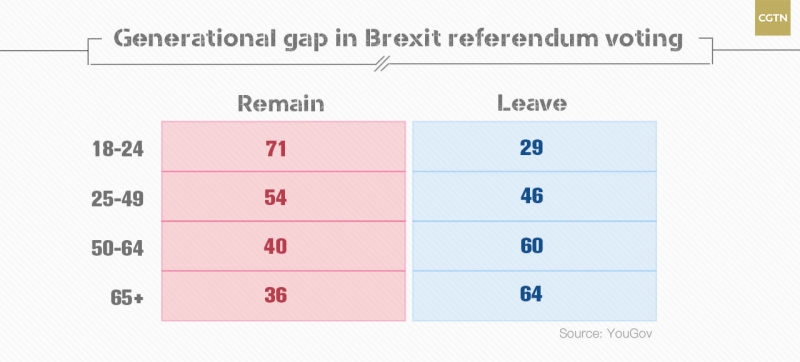

The damage Brexit could do to future generations of Britons – particularly those that didn’t have a vote in the referendum – has been taken up by young campaigners. Our Future, Our Choice is echoing an argument made by former Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg that by the time Britain has left the EU, Remain voters will likely outnumber Leavers (over 65s voted disproportionately in favor of Brexit). this has led many to argue that even if Brexit is not overturned, the parting deal with the EU must be in line with the views of younger generations.

Can Brexit be stopped?

Conventional wisdom suggests that while Brexit could be overturned, it’s very unlikely to happen. Opinion on Brexit has shifted towards indifference rather than revolt as the process has dragged on, but there has been no sign of a significant polling swing in favor of Britain staying in the EU.

Politicians hoping to overturn Brexit have always targeted the final leg of negotiations as the key period, however. Over the next few months there could be several key pressure points:

Britain's Prime Minister Theresa May arrives at the European Council headquarters on the second day of a summit of European Union (EU) leaders on March 23, 2018, in Brussels. /VCG Photo

Local elections

Britain will hold local elections on May 3 which current polls suggest will lead to a wipeout for the Theresa May’s Conservative Party in London. such a result would pile pressure back on the prime minister, and likely again raise talk of a leadership challenge. May has shored up her position with a well-received response to the nerve agent attack in Salisbury, but the credit she has earned could quickly disappear if the Conservatives perform poorly. A new prime minister would likely mean a new approach to Brexit, and demands for fresh national elections – at that point, anything could happen. Talk of a new centrist, anti-Brexit political party being set up is constant.

Parliament vote

The British parliament has been granted a “take-it-or-leave-it” vote on the final Brexit deal, provisionally set to take place in October 2018. The move was a concession from the government, but offers little room to maneuver – accept the terms, or leave without a deal. Whether it would be so simple in practice is unclear – especially as a “no deal” vote is considered to be the most damaging option for the British economy. Voting the deal down could throw open new opportunities. Amendments, including on continued membership of the Customs Union, could also see the government voted down.

Second referendum

The prospect of another referendum fills many Britons with dread, but there is a strong argument that the binary "yes" or "no" choice in 2016 didn’t address the complexities of Brexit. Many of the protesters at the weekend demonstrations are likely to call for another vote. Some senior figures, including former prime ministers Sir John Major and Tony Blair, have argued that voters should have a say on the final deal agreed by Britain and the EU. The current prime minister has ruled out the possibility – but the situation could change with events.

Traffic crosses the border into Northern Ireland from the Irish Republic alongside a Brexit Border poster on the Dublin road Co Armagh border, between Newry in Northern Ireland and Dundalk in the Irish Republic, December 1, 2017. /VCG Photo

Europe split

Much of the focus of the Brexit negotiations has been on Britain – Theresa May must strike deals within her party, within the country, and with the EU. The EU has so far remained publically united, but Britain has been looking to pick off countries with specific requirements to weaken the EU’s negotiating position. There are also areas – notably the Irish border – where the sides are far from agreement. No deal could mean Britain leaving on World Trade Organization rules – or Britain extending a transition period indefinitely.