For years, app developers have been complaining about Chinese consumers’ indifference to chargeable services on their mobile devices. A recent squabble over a leading local dictionary brand’s strategy to charge its users suggests that the free-ride culture may have started to dry up.

CFP Photo

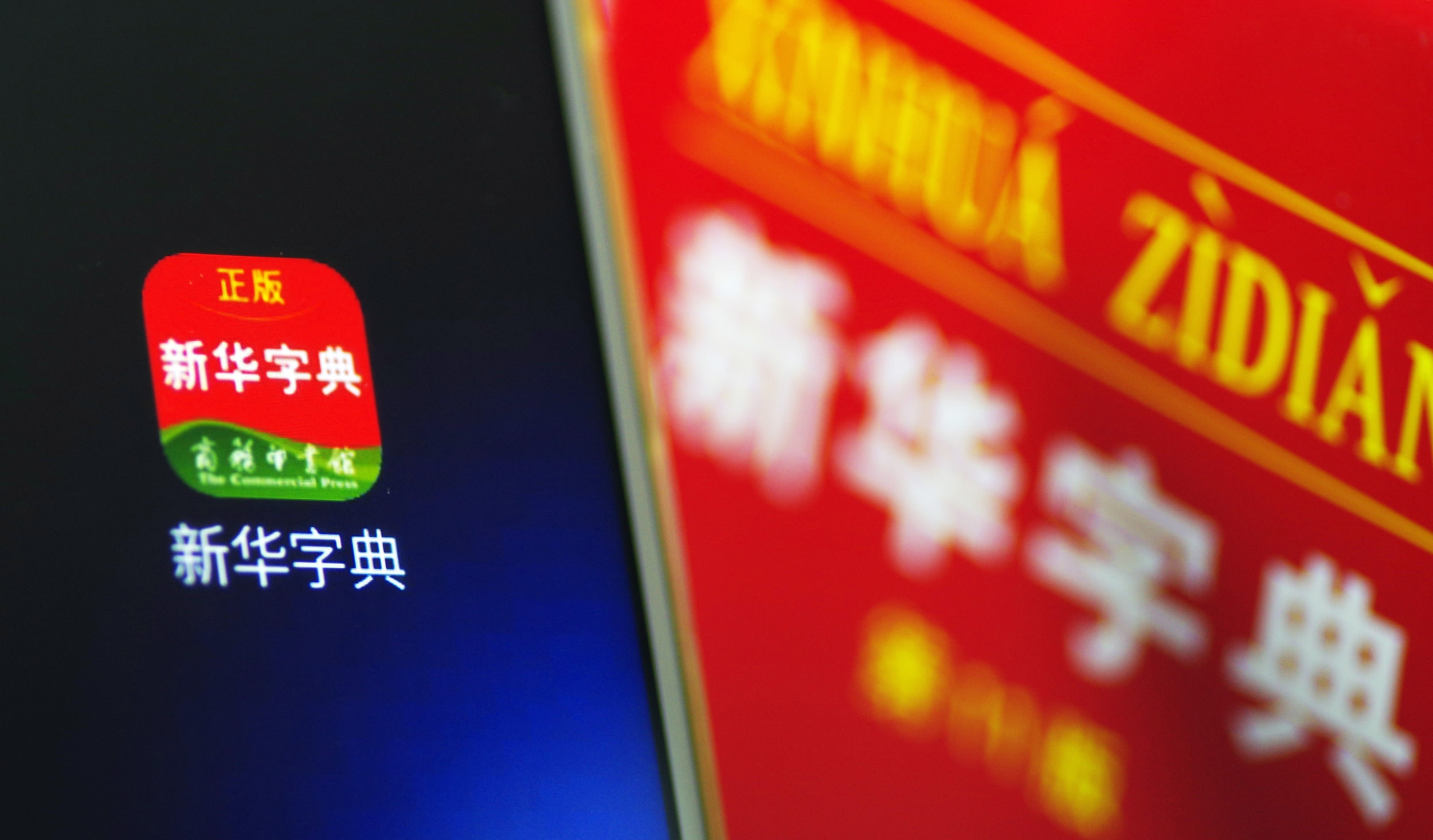

Xinhua Dictionary, a 60-year-old brand, rolled out its digital version on Sunday that charges at least 40 yuan with two free searches per day, more expensive than the paper editions sold online.

Criticism soon broke out at its launch, with many discontent users calling the pricing irritating given the cheaper paper editions and the similar services on the Internet that are free. Some have gone on to accuse the developer of being so profit-driven that it had damaged a long respected brand.

Voices that questioned the quality of the app also surfaced.

The app’s developer, a firm based in Shanghai, responded on Wednesday morning, saying it has suspended service bags which would charge users for more than a hundred yuan and begun to fix bugs.

“Taking the copyright and the developing costs into account, the firm believes the pricing is reasonable,” the firm told the Shanghai-based Jiefang Daily.

July 2016: A saleswoman at a local bookstore shows schoolchildren how to tell a genuine dictionary from fake ones in Anhui Province. Xinhua Dictionary is a household brand in China, with generations of Chinese people going to primary school with a copy. /CFP Photo

But the tide was soon turned online. The criticism has been overwhelmed by support to the idea of chargeable digital applications.

On China’s Twitter like Weibo, many have spoken out siding with the app’s developer, a tech firm based in Shanghai, calling for their fellow consumers to put to rest the “obsolete” conception of free rides.

“Good services do not always come out free and you have to grow up to adapt to that,” commented a Weibo user.

“If you are willing to top up your mobile video game account with a hundred yuan, you can certainly afford a dictionary that charges you only 40,” another commented on Weibo.

CFP Photo

The loud and clear support displayed across Weibo, on which there are around 300 million active users, may prove to be music to both domestic and overseas developers, who are worried by the long established pre-occupation that Chinese consumers are not willing to dig in their pockets for an app specializing in putting content/knowledge a fingertip away from consumers.

According to a share-economy research body in China’s National Information Center, China’s knowledge market, whereby participants distribute knowledge resources for profits is likely to embrace a huge boom. In 2016, the net worth of the entire market was around 61 billion RMB, rising by 205% year-on-year.

A report by 36 Kr, a Chinese consulting firm, predicted that knowledge consumption is likely to generate more than 30 billion yuan in 2017.