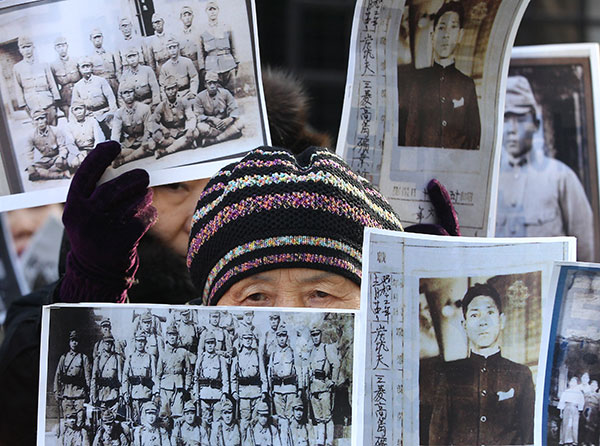

A South Korean woman whose family members were killed by Japanese forces during World War II attends a rally in Seoul on Monday demanding full compensation and an apology from the Japanese government. AHN YOUNG-JOON/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The landmark deal Japan and the Republic of Korea signed on an "irreversible" resolution to the so-called comfort women issue on Dec 28 has taken a twist within days. Under the accord, the Japanese government will provide 1 billion yen ($8.3 million) to a fund the ROK government will establish to support former "comfort women". In return, Japan has demanded that the ROK not raise the issue again.

Japanese news agency Kyodo News quoted a government source as saying the money paid by Japan to the ROK fund is contingent on removal of the statue of a girl-which was installed in remembrance of the "comfort women"-in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul. Japan has called the statue an affront to its national dignity.

Japan coined the term "comfort women" to refer to young women who were forced into sexual slavery by Japanese soldiers before and during World War II. These women were from countries and regions such as Korea, the Chinese mainland, Taiwan and the Philippines. Most of them were Korean, with a small number of them being Dutch and Australian. And they were the victims of the largest human trafficking case in the 20th century.

The wartime sex slavery issue had long strained Japan-ROK ties and raised concerns even in the United States.

For long, Japan considered it had fulfilled all its postwar obligations to the ROK via a 1965 treaty that came with $800 million in economic aid and loans. But despite that Abe took a U-turn and agreed to the pay for the ROK fund for "comfort women", because, as some experts say, Tokyo and Seoul both were under pressure from their main ally, Washington, to resolve the issue. More importantly, the US and Japan want to build a strong front against China, and the resolution of the "comfort women" issue is likely to lead to expanded military cooperation among the US, Japan and the ROK.

But Japan's sincerity is now in question, because it wants to link its payment to the removal of the statue. In response, ROK Foreign Minister Yun Byung Se said Seoul will urge Tokyo to refrain from behaviors "that could cause misunderstanding".

The removal of the statue was not mentioned as a condition for Japan's financial aid in the joint announcement by Yun and his Japanese counterpart Fumio Kishida after their talks in Seoul.

The people of the ROK, including the surviving "comfort women" protested against the deal, saying Abe's apology did not acknowledge the extent of the Japanese military's involvement in the forced prostitution program nor did he detail the atrocities committed by the Japanese military.

It is too early to assess the impact of the deal.

Japanese ultra-right groups-which deny the Imperial Japanese Army's involvement in wartime atrocities may seek to undermine support for the agreement. Worse, Abe's wife Akie Abe visited the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, which honors 14 Class-A war criminals along with millions of Japan's war dead, on the same day that Japan and the ROK agreed on the accord on "comfort women".

Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida has called the deal a project to recover the honor and dignity of all "comfort women" and to heal their emotional wounds. Therefore, the amount Japan is willing to pay the ROK should not be hush money. And Japan's acceptance of its war history should not stop at the ROK.